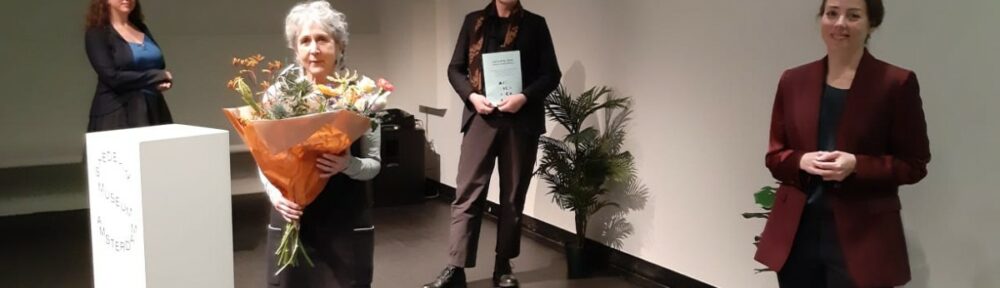

Dinsdag 2 maart kende AICA Nederland de AICA-Prijs toe aan de tentoonstelling 'Walid Raad – Let's be honest, the weather helped' die in de het Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam te zien was. Hripsimé Visser, curator van de tentoonstelling en directeur van het museum Rein Wolfs ontvingen de prijs van Joke de Wolf, voorzitter van AICA Nederland. De uitreiking, inclusief het vraaggesprek met de curator, is hieronder als video terug te kijken. Onafhankelijk curator en criticus Nat Muller sprak tijdens de uitreiking een laudatio uit, ook die is terug te zien en onder de video terug te lezen.

Laudatio door Nat Muller

Dear Rein, dear Hripsimé, and everybody watching the live stream at home,

It is a true honour and privilege to give this laudatory speech on behalf of AICA for Walid Raad’s solo exhibition Let’s be honest, the weather helped. I speak to you in strange times when the memory of a visit to a museum seems very distant indeed. Looking back at this exhibition and considering the predicament most of the world finds itself in today, we have much to learn from Walid on how to find sense in nonsense, meaning in the incomprehensible, and how to work with, and through, disaster. But perhaps mostly his exhibition Let’s be honest, the weather helped shows that a heavy and serious subject matter, often of the political and historical kind, can sometimes best be accessed through an imaginary, with lightness and irony, rather than under an oppressive weight.

That is not to say that this retrospective lacks gravitas. On the contrary. Gravitas comes at us from many different sides. And though it has a lingering presence, it ultimately is transformed into something else. Whether the works’ subtext is Lebanese politics and how years of civil strife have scarred a society and produced a collective amnesia; whether it is the dark entanglements between neoliberalism, petro-dollars, exploitative labour, and contemporary art; or whether it is an effort to decolonise and broaden art historical scopes. The viewing experience is never didactic. Rather, as the viewer wanders from room to room and encounters sculptures, paintings, photographs, diaries, notebooks, and video, the experience is one of wonder and estrangement and an invitation to look differently. It is as if the artist has catalogued what is broken in the world and has devised a way to try and fix some of it, however imperfectly.

On display then — and to me this not only rings true in the works, but in the exhibition as a whole — is an idea that out of loss something can be crafted and restored. This mindset becomes particularly urgent and relevant today when so much is in need of repair. If an art object lacks a shadow, then provide it with a prosthetic one and eventually its real shadow will return, as happens in the series Scratching on things I could disavow (2012-2017). Or as in the stage sets of Les Louvres and/or Kicking the Dead (2019), if “undead” artworks in a collection lack a mirror image and keep returning to their storage, then paint a copy of their missing reflections on their crates to repel them and lure them away to landscapes more attractive than theirs. At the centre of this always stands an artwork, a document, a memory, a story, compelling us to carry away our own cracked reflections.

Hovering over the exhibition, there is also that old, but quite tricky, curatorial dilemma of how to navigate the representation of politics (transnational, American, Arab, Lebanese) and the politics of representation (an Arab artist in a Western institution). In particular for an artist like Walid Raad whose oeuvre is acknowledged and well-known in the Arab world, and to professional and wider audiences globally. But not necessarily in the Netherlands, where artists from the Arab world still get little exposure. It takes a rare artist of Walid’s calibre, but equally careful and sensitive curation, to manoeuvre this.

The context of the Lebanese Civil War (1975-1990) during which Walid came of age is formative for much of his practice, especially that of the Atlas Group, and continues to be so, as unresolved issues still rekindle violence and division after thirty years. The 2019 uprising against ongoing corruption, social injustice and Lebanon’s downwardly spiralling economy; the devastating blast in Beirut’s port on 4th of August last summer; and only three weeks ago on the 4th of February, the assassination of the political activist, filmmaker and publisher Lokman Slim, all serve as painful reminders of how volatile the situation is. But while car and aerial bombs, explosives, bullets, hostage tapes, militias, botched post-war urban reconstruction, and regional and international figures, all have a part to play in the Lebanese wars, here in the exhibition, they unearth other narratives.

Fact twists into fiction, fiction into fact. Archiving and Walid’s forensic sleuthing become acts of preservation, of memory making, but equally of creative disobedience refusing a singular interpretation of factual or fictional events, be they from the past, the present, or even from the future. In other words, if an audience expects to learn more about Lebanon and its wars, these works, and by corollary the exhibition, refuses to meet them. And yet in a strange and winding way, it tells you all you need to know by turning the bizarre into the most meaningful.

A solo show always has a different dynamic than a group exhibition, not only in how it unfolds to an audience, but also how artist and curator collaborate. It seems to me that Walid’s conceptual method has served as the prime curatorial, and if we look at the catalogue also editorial, logic. I love this idea of citation, which in curatorial practice does not happen nearly enough. There are no highly convoluted curatorial texts framing the exhibition, there are no tick-box diversity brownie points to be scored, and there is no pedantic taking of audiences by the hand. How refreshing! Rather, the emphasis is on the life of objects and how their form, aesthetics and strange and often contradictory ways of being in the world, tell us stories. Of note here is how the live walkthrough performance Les Louvres and/or Kicking the Dead activated the exhibition and brought in an additional layer to unravel. The performance was not a one-off public event, but structurally staged multiple times over the duration of the exhibition as a seminal part of it. If you will, it provided the life blood coursing through the veins of the exhibition, introducing further themes and tangents. This is a really interesting way of highlighting the performative aspects already scripted in the artworks, as well as facilitating multiple tête-à-têtes with the artist.

The latter is certainly not a given in large institutional contexts. In the walkthrough the objects came to life differently, in relation to and in conversation with the artist and all those present. For example, it was intriguing how the stage sets of Les Louvres and/or Kicking the Dead functioned primarily as props during the walkthrough and then reverted back to being an art installation afterwards. The whole set-up with the performance felt a bit as if we were being let in on a secret and became a select group equipped with extra knowledge of how to tackle the various works in the exhibition. As seats to the performance were limited and rapidly sold out, this is, at least from an institutional perspective, quite a risky strategy to take for such a crucial component of the project. Still, I am glad this risk was taken, for it not only speaks to the fact that every museum visit is different, but it also cheekily underlines that the difference between knowing and not knowing is, to use Walid’s phrasing, “thinner than a hair.”

This brings me to my final point and the murky subject of institutional critique. In a body of work like Scratching on things I could disavow criticism is playfully, yet firmly, reserved for the autocratic monarchies of the Gulf where modern and contemporary art, whether through franchises of Western institutions like the Louvre or the Guggenheim, or, through other machinations of the art market, have become an instrument for soft diplomatic leverage.

I want to stress, however, that in Let’s be honest, the weather helped no one remains unscathed. On the one hand, there is the anticipatory caveat that with shrinking public budgets more Western museums and universities might be seduced to set up shop in the Gulf without calibrating the effects of censorship or the exploitative labour of migrant workers on their brand and the content they intend to convey. On the other hand, there is a subtle j’accuse of how Western art history and museum collections, still largely ignore the greats of modern and contemporary Arab art. This is best articulated in the series of works showing paintings of the well-known Syrian modernist painter Marwan (1934-2016), allegedly found on the back of paintings in storage at the museum. This again refers to my earlier point of knowing and not knowing. Is this a real artist or not, and even for those of us who do recognise the style of Marwan, are these paintings real or fake? After all, we are in a Walid Raad exhibition. The joke is most definitely on us. Walid, himself a great of contemporary art, makes a salient point here. Namely, that in art as in life, we build on the past, ours and that of others.

In the Netherlands the work of artists from the Arab world is underrepresented, especially when compared to neighbouring countries. Too often their work is reduced as flatly illustrative of the politics of the day, be it war, conflict, or revolution. Too often their oeuvres are read through the narrow lens of orientalist identity politics that Others their practice and reduces it to socio-political punditry, rather than folding it into a conversation about art, as well as many other possible conversations.

I therefore commend the Stedelijk for putting on a solo show that so thoughtfully and genuinely carries the artist’s voice. Especially, if that voice, as is the case with Walid’s, is inflected with a variety of linguistic, geographical, and artistic accents, doublespeak, and references. Let’s be honest, the Weather Helped manages to be an exhibition in which the ghosts of history, as well as those of the present, haunt us strangely and wondrously, even after we exit the museum.

I sincerely hope that this AICA Prize is further encouragement for the Stedelijk, and other Dutch museums and institutions alike, to show the work of artists from the Arab world prominently, fiercely, imaginatively, and without compromise.

Again, on behalf of AICA, its jury, and AICA members, my very warm congratulations,

Nat Muller